Sue de Beer (born September 8, 1973 in Tarrytown, New York) is a contemporary artist who lives and works in New York, New York.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sue_de_Beer

Laura Parnes is an artist whose work engages strategies of narrative film and video art to blur the lines between storytelling conventions and experimentation. Parnes combines elements such as continuity and dialogue with highly stylized sets and performances to present non-linear narratives as installations that utilize the architectural space of a gallery or museum. By deploying cinematic citation as an element of site-specific installation, the staging of her own productions reverberates in an exhibition setting, often requiring the audience to physically enter a scripted environment or re-creation of the production set. Parnes’ installations operate at a symbolic and sculptural level, while maintaining a narrative coherence that points to a future in which reality is tightly nested in layers of art, popular culture, and experience.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laura_Parnes

Heidi 2, produced in collaboration with Sue de Beer, is a feminist revision of Mike Kelley and Paul McCarthy's 1992 video, Heidi. This intentionally low-end production illustrates the way B-movie aesthetics can be employed ironically to comment on cultural depravity. This mother/daughter story reclaims patriarchal abjection through reinterpretation. The work is introduced through a disturbingly humorous birth scene. From there, the pair's daily life gradually moves from bulimic contests and sexual play to technologized degradation. This relationship implodes in the final scene when the daughter, Heidi 2, surgically implants a TV set into her own abdomen with her mother's help. The TV contains a live feed of herself. Aesthetically, the cold Cronenberg-esque silences distill the horror of transmitted self-objectification particular to the adolescent female.

Laura Parnes

http://www.lauraparnes.com/heidi.html

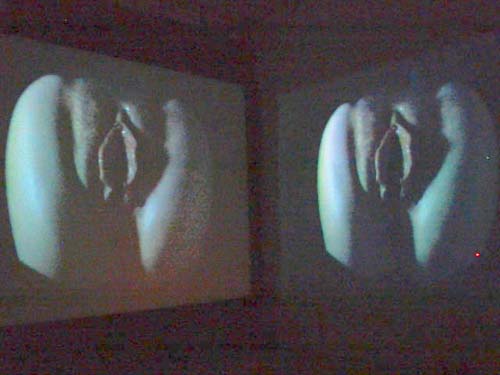

Cathy Lebowitz: So Josefina, what happened first in the film?

Josefina Ayerza: Well, what happened first was this birth. It was a big thing that happened. In the way it was presented. This enormous vagina… very impressive. And also in the sense that this vagina was so active in itself… so as to push this thing out of itself. And you could see this activity there under your eyes. I liked the way they set up the expectation… the time for something to appear… till the head pops out. Of course I could see the rejection in the faces of other people, trying to run away.

C: Because when the baby comes out, it's not a pretty baby.

J: I was amazed to see this. I never saw my babies by the way, because at this very instance there is no mirror in front of you when you have a baby. You're just pushing. You don't see it in a mirror, that's the only way to really see that moment. You can only see it in somebody else. In the movie, it's a horrible thing that comes out, I would say.

C: Like an alien.

J: Like an animal. It looked like a piggy I would say this one.

C: So you think this vagina is Heidi's and she is having a baby Heidi?

J: I was thinking is this a real thing? Is it a real vagina, and is it a real photograph of a birth? Since I never saw a birth… I think it is not true that it is so tremendous…

C: Wasn't the vagina moving or talking? I don't remember. There were some words.

J: The vagina I don't think was talking. There was a voice-over with words spoken. But it was active, very active. Also I was impressed by the color, it was white what came out of there.

C: The baby, you mean?

J: The baby is inside of placenta. And you could see this.

http://www.suedebeer.com/heidi2_2.html

In their 1992 video Heidi, artists Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley turned the classic tale of a young girl’s coming of age into a three-ring circus of family dysfunction. In this orgy of obsessive-compulsive behavior interspersed with lofty Socratic dialogues on the relationship of nature and culture, Grandpa, a sadistic paternal figure, teaches Heidi and her brother Peter what they need to know to grow and thrive in the adult world; how to read, how to get beaten up, how to push sausages out of your ass. Now New York-based artists Laura Parnes and Sue de Beer have given the story a media-saturated spin in a two-channel video installation titled "Heidi 2" As the script notes the new production “is not a critique or on homage but a sequel, and follows the roles of any good sequel: more blood, additional celebrities, and more special effects”.

The video begins with a disgusting birth scene suggesting a cross between Cindy Sherman’s sex toy photos and the monster births in Larry Cohen’s "It’s Alive" films. The character of Heidi later appears as both mother and daughter, played by the two artists in rubber Charlie Brown and Pigpen masks, Grandpa is reduced to a bit player and Leonardo de Caprio (an actor in a cardboard mask) fulfills the celebrity quota. Mocking parenting in the age of rampant bulimia and art school instruction in the age of Abjection 101, Heidi 1 shows Heidi 2 how to projectile vomit (“Like this?” daughter asks—big splash—”No, that’s too self-conscious” mom replies) and at the climax of the tape, how to “self-operate” In this disturbingly affectless scene (combining radical weight-reduction surgery with Teletubbies-style auto-surveillance) Heidi 2’s stomach is cut out, tossed into a bucket, and replaced with a TV monitor carrying her image in a continuous live feed.

To those familiar with the artists work, Heidi 2 is an intriguing marriage of sensibilities. Parnes’ video "No Is Yes". 1998, limns a more straightforward (but equally depraved) narrative in which two teenage girls murder a misogynist punk rocker in a "Thelma and Louise"-style face-off, give him a "Clueless"-style makeover (stripping him nude, tying him up, adorning him with knife inflicted scratch-iti), and then ask their mentor, a dominatrix named Sarah, for "Pulp Fiction"- style help in disposing of the body. (“Who do you think I am, Harvey Keitel?” Sarah asks). Enlivened by quick editing and MTV-style inserts, "No ls Yes" is a teen rebellion film reinterpreted far a gallery context and its bleak message—that rebellion in a world of commodified nihilism is meaningless—echoes throughout "Heidi 2".

De Beer, in her own solo work, has a flair for catchy, surrealistic images, resembling the shock iconography of fashion and advertising (e.g. Diesel’s recent “dead teenagers” campaign) but with a creepy, personal vibe. Through low-budget f/x, including digitally altered videos and C-prints, she has depicted herself as a pair of clones in a languid make-out session, an ax-murder victim split from skull to sternum, and an impossibly long-legged Frankenwaif straining to touch the floor with her fingertips. Although arrived at collaboratively with Pames, Heidi 2’s vomiting scene—with its doppelganger composition and obvious "Exorcist" reference—recalls de Beer’s characteristic union of horror-movie scenes and choreographed body art pathologies.

This immersion in media and popular culture sets Parnes and de Beer apart from an older generation of performance artists (McCarthy, Schneeman, Nitsch), who seek to heal a split between a “repressed, cultural” self and an “authentic, natural” self through ritualistic acts of transgression (fecal smearing, orgiastic sex, and so on). In de Beer’s and Parnes’ view, no split exists because everything is mediated: the most extreme acts can be found on tape at the corner video store and “real” experience is suspect. Rejecting the superior vantage point of the artist/shaman, the artists use pop culture tropes without apology; expressing the most “primal” events—childbirth, orgasm, incestuous rape— in the idiom of sitcoms, video games, and splatter films.

Tom Moody

http://www.suedebeer.com/moody.html

Heidi 2 was billed as a sequel to Mike Kelley and Paul McCarthy’s Heidi (1992). It is not uncommon for a sequel to be handed over to a new director, often a hack who takes the original’s most salient features and then exaggerates them. This is especially the case in the horror and sci-fi genres, in which the sequel promises more abundant gore, updated technology and cameo appearances by current or fading celebrities. De Beer and Parnes make overt references to this paradigm. Aside from the pressures of re-telling a familiar story and following in the footsteps of a recent film, they confront the anxiety of influence that is particularly pronounced in the art world - it could be said that Kelley and McCarthy are contemporary art’s equivalent to film directors such as Wes Craven or David Cronenberg.

In Kelley and McCarthy’s Heidi, Grandfather is a raging, abusive character who controls the household and trains Heidi in the lessons of life. The dull-witted shepherd boy, Peter, is the frequent object of Grandfather’s sadism. Perhaps concerned about an oedipal take-over of the family, Grandfather keeps him helpless and mute. De Beer and Parnes turn the tables and portray the old man as a couch potato who seeks male companionship from Peter. Despite one scene in which Grandfather (played by Guy Richards Smit) spanks Heidi - launching her into a flight of fantasy - his role has been reduced to that of a struggling has-been. Are Kelley and McCarthy meant to be equated with Grandfather? If so, Heidi 2 is more than a sequel: it takes on the quality of a revisionist history. In this extension of the Spyri narrative, Heidi 2 (performed by De Beer) gets her education from her mother, Heidi 1 (performed by Parnes), who teaches her to perform an auto-abortion, a scene which satisfies the bloody requirements of the sequel. Yet by preventing the birth of what might have turned out to be Heidi 3, De Beer and Parnes seem to pre-empt the possibility of a trilogy.

De Beer and Parnes’ commentary on the film industry targets movies like Disney’s Heidi (1993), which starred Jason Robards as Grandfather and Jane Seymour as the nanny. It takes good actors to enliven out-dated roles and so de Beer and Parnes cast Eric Heist as Leonardo Di Caprio (Heist wears a Leo mask), who in turn plays the part of Peter. The shepherd is now Heidi’s love interest and apparent father of the aborted child. Having removed the threat of an offspring, Heidi 2 and her mother fill the void in her belly with a television monitor - just like the Teletubbies. Unlike the Heidi of the novel, who rejects big-city life in favour of a healthy rural existence, Heidi 2 wholeheartedly embraces the trappings of culture.

De Beer and Parnes bring the saga further up to date through a Hollywood-style merchandising campaign. Accompanying the movie are blood-red posters and grotesque knee-high dolls and accessories that come in vacuum-packed containers. It’s an approach which has a parallel in the art world, since it is now common practice for artists working in film and video to produce multiples and sell photographs in order to fund their large-scale projects (Matthew Barney is the undisputed king of this strategy). By ‘branding’ their product, the artists seem to be attempting to usurp the terrain formerly occupied by Kelley and McCarthy. Firmly ensconced in the gallery and art school systems, these established artists have come to represent for De Beer and Parnes the repressive authority figures who have to learn to accept the presence of youthful exuberance - just as Grandfather learned to love Heidi.

Gregory Williams

http://www.frieze.com/issue/review/sue_de_beer_and_laura_parnes/

No comments:

Post a Comment