Adolph Frederick Reinhardt ("Ad" Reinhardt) (December 24, 1913 – August 30, 1967) was an Abstract painter active in New York beginning in the 1930s and continuing through the 1960s. He was a member of the American Abstract Artists and was a part of the movement centered on the Betty Parsons Gallery that became known as Abstract Expressionism. He was also a founding member of the Artist's Club. He wrote and lectured extensively on art and was a major influence on conceptual, minimal art and monochrome painting. Most famous for his "black" or "ultimate" paintings, he claimed to be painting the "last paintings" that anyone can paint. He believed in a philosophy of art he called Art-as-Art and used his writing and satirical cartoons to advocate for abstract art and against what he described as "the disreputable practices of artists-as-artists".

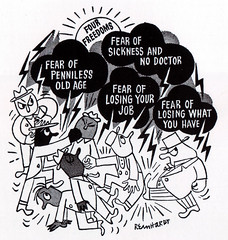

Reinhardt joined the staff of PM in 1942 and he worked full-time at this daily newspaper until 1947, with time out while drafted for active duty in the U.S. Navy. While at PM he produced several thousand cartoons and illustrations most notably the series of famous and widely reproduced How to Look at Art series. Reinhardt also illustrated the highly influential and controversial pamphlet Races of Mankind (1943) originally intended for distribution to the U.S. Army, but after being banned subsequently sold close to a million copies. He also illustrated a children's book A Good Man and His Good Wife. While attending Columbia University he designed many covers and illustrations for the humor magazine Jester and was its editor in his senior year (1934–35). Other commercial art work was done "for such varied employers as the Brooklyn Dodgers, Glamour magazine, the CIO, Macy's, The New York Times, the National Council of American-Soviet Friendship, The Book and Magazine Guild, the American Jewish Labor Council, New Masses, the Saturday Evening Post, Ice Cream World, and Listen magazine. He also illustrated many books such as Who's Who in the Zoo.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ad_Reinhardt

Circa 1946

However hermetic Reinhardt’s black paintings may seem, they were not created in a vacuum. The kind of profound, self-reflexive abstraction he advocated was partially a product of, and reaction to, the climate of Cold War America. Despite the iconoclasm of his aesthetic discourse, Reinhardt was actively engaged in political and social issues throughout his life. During the early 1940s, his editorial cartoons appeared in the leftist newspapers The New Masses and PM. Later, he participated in the antiwar movement, protesting against America’s involvement in Vietnam, and donated his work to benefits for civil rights activities. An aesthetic moralist, Reinhardt sought to create an art form that—in its monochromatic purity—could overcome the tyrannies of oppositional thinking.

Nancy Spector

http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/collections/collection-online/artwork/3698

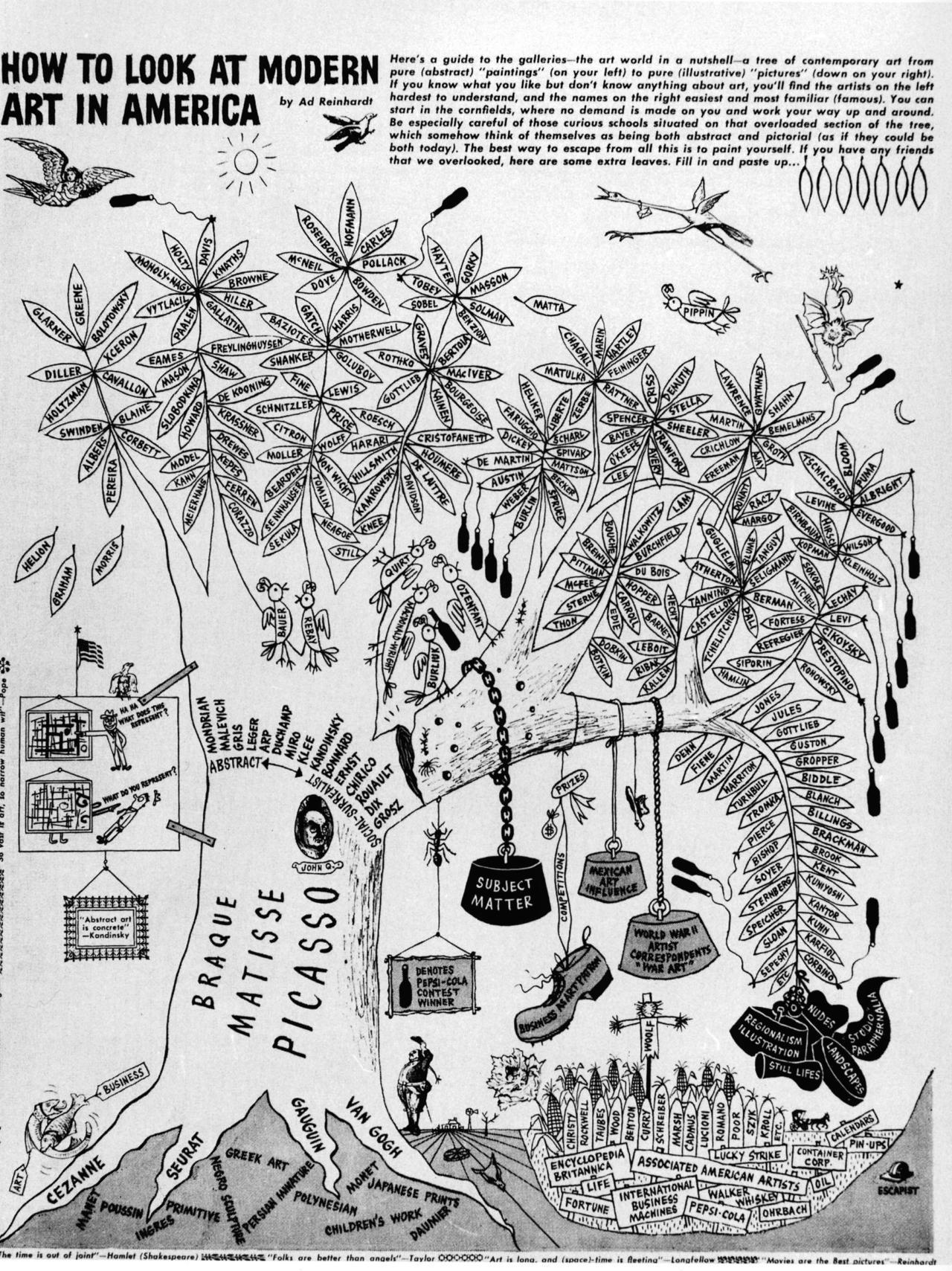

How to look at Modern Art in America, 1946

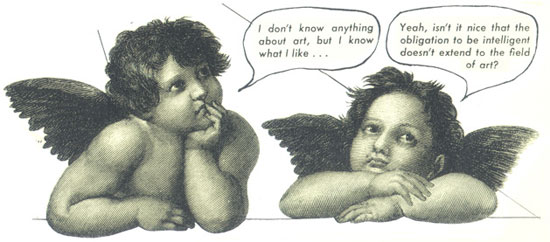

Reinhardt is largely known for his abstract expressionist paintings, but he also published a series of satirical cartoons around that time period. The Reinhardt cartoon, titled "How to look at Modern Art in America," was a response to a diagram that was circulated a decade earlier, attempting to explain cubism and abstract art

Reinhardt's satirical response was apparently very popular among artists and hung in studios all over America for many years. I love coming across these little known bits of art history--it would be fun to see a version about the current state of affairs--especially in the post-Pop art era.

Hilary Pfeifer

http://hilarypfeifer.blogspot.co.uk/2008/07/how-to-look-at-modern-art-in-america.html

The Races of Mankind, 1943

Long before Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Rauschenberg took shots at the high-mindedness of the postwar American avant-garde, Ad Reinhardt (1913-67) was blasting away from a privileged vantage in the middle of the fray. A wise-cracking contrarian whose penchant for dialectics would not allow him to hold any position he could not later undermine, he was a consummate art-world insider and a fierce defender of abstract painting. At the same time, his ingrained populism made him suspicious of the rhetoric and institutional power brokering that supports any art elite.

As examples of the kind of blather that can still be overheard in cafes and galleries and art schools, Reinhardt's cartoons are still timely as satire. But they may be even more valuable for capturing the high spirits of a wily provocateur and his hot-house milieu. The Pop artists weren't the only ones who knew how to have fun.

Richard B. Woodward

http://www.nytimes.com/2003/12/21/arts/art-architecture-ad-reinhardt-newspaper-cartoonist-the-abstract-double-agent.html

No comments:

Post a Comment